Something I’ve thought about recently is the importance of distinguishing the difference between sympathy and empathy, and how it relates to chronic illness. Once you understand the difference between the two, you’ll understand why we’re looking for your empathy, not your sympathy.

Most people don’t really think about what each of them mean, and probably don’t know the difference themselves. It’s something that I remember learning in English class in high school or college, and it’s something that I’ve tried to keep in the back of my mind since.

As similar as the two are, the are quite different in feeling. The two words share a common root word, “pathos”, which means feelings, emotions, or passion.

Sympathy vs. Empathy

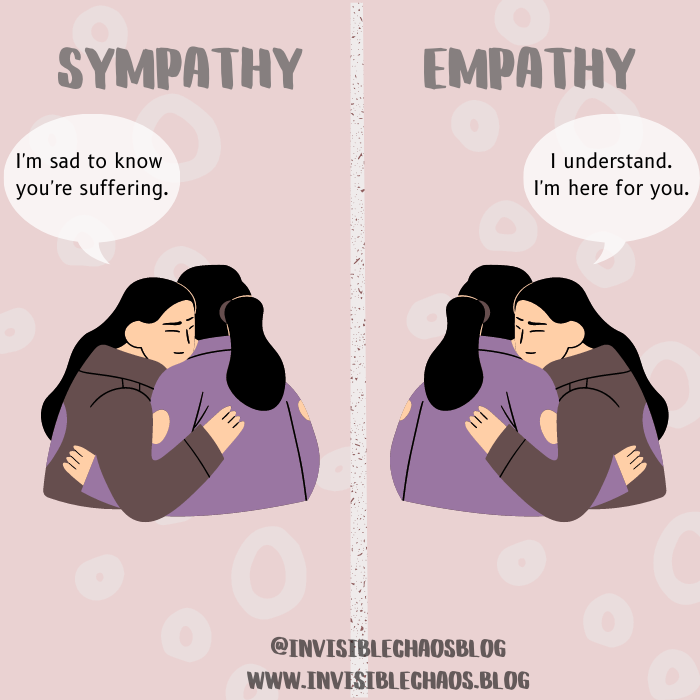

Sympathy is when you share the feeling or experience of someone else– it’s usually something you yourself has felt or experienced at some point in your own life. The keyword in the definition of sympathy is “shared”, it’s a big part of what separates it from empathy. The prefix “sym” in sympathy is Greek, and means together, or at the same time.

The emotions you may experience along with sympathy include compassion, sadness, and pity. For example, when someone you know is grieving after a death, you send your condolences, or your sympathy. This is your way of saying you are sad along with them, because when they are grieving, you are grieving with them, sharing their pain and sorrow.

Empathy, on the other hand, is the ability to understand or imagine what it’s like to be in the other person’s situation. With empathy, you are putting yourself in the other person’s shoes. Where sympathy is about sharing, empathy is about understanding.

Why am I getting into the definition of sympathy and empathy? Because it’s something that comes up quite a bit when you’re chronically ill, and few people have actual empathy for us, and instead, feign (unwanted) sympathy. Those who should have empathy, like doctors, often do not.

We Want Empathy, Not Sympathy

When you’re chronically ill, sympathy is usually shown in the form of pity. Instead of trying to make us feel better about things, or showing us they’re there for us, people will make us feel worse by giving us pity, which is unwanted. We don’t want you to feel bad for us, we want you to understand us.

Sympathy involves understanding from your own perspective, which can make it seem like it’s about you instead of it being about the other person, which is the whole point of showing them compassion in the first place. As mentioned above, sympathy is something that is shared, and usually something experienced by the person who is showing sympathy to the other person. With that in mind, those who are showing us the pity and sympathy often feel like they need to try to relate to us, and often they cannot.

When you can’t relate, it just makes us feel that much worse about it. We don’t want to hear that you’re tired because you slept badly last night, it’s not the same as the deep fatigue we feel. Fatigue is not the same as being tired, we wish it was that simple. We don’t want to hear about the time you had the flu and couldn’t get out of bed for a week, it’s not the same as us being bedbound for years.

We know you’re trying to connect with us and trying to make us feel better, but it often does the exact opposite of what you’re intending.

Don’t get me wrong, that doesn’t mean you can’t share your own feelings and experiences with us. Empathy involves that as well. But please, unless you’re actually chronically ill, don’t equate an average, normal feeling or illness to something that we have to live with every day of our lives until the day we die. Chronic means ongoing, and it will be with us forever. I’ll never not be exhausted and fatigued, no matter how much sleep I get.

Empathy is all we’ve ever wanted. From friends, from family, from teachers, from doctors. We want to be understood, above all else. A little compassion goes a long way.

There is a time and place for sympathy, but when speaking to a friend or family member who is chronically ill, go with empathy instead. It will be more genuine for both parties.

A lot of us have lost a lot to chronic illness, and we’re constantly grieving multiple things– the lives we once had, our former healthy selves, the loss of friendships, the loss of income, the loss of our ability to do certain things. There’s a hundred things I could probably list that I’ve lost over the years, and it doesn’t get much easier over time. I talk about it in a blog post I wrote a couple months ago, about the Grief Loop we live in. Give it a read if you haven’t already read it, it may give some insight.

It’s bad enough when friends and family don’t have any empathy for what you’re going through and experiencing, but when doctors don’t have any empathy (and many do not), it’s a whole other story.

Doctors Lacking Empathy

The medical gaslighting could come into play at these moments of apathy (which is defined as the lack of interest, concern, or enthusiasm of others). Sometimes you’ll be brushed off, or told “it’s all in your head”. It’s something nearly everyone with chronic illness has experienced, which is astounding, but true. We’ve heard it all over the years.

Being medically gaslighted for years leads to lasting effects and has consequences. It’s not something you just forget, that’s for sure.

According to a survey, 71% of patients have felt a lack of compassion when speaking to their doctor or medical professional. I’m not surprised by this number, but I’m actually surprised it’s not higher. There’s a reason that people won’t go to doctors, and lack of trust and lack of empathy is part of the reason.

Whether the result of being in practice for a number of years, or because they never had empathy to begin with, it’s never okay for a doctor to have a complete lack of compassion and empathy. It makes you feel dehumanized, and less than– like we don’t matter.

Compassion Fatigue, “The Cost of Caring”

The term known as “compassion fatigue” was coined in 1992. Compassion fatigue is a condition characterized by emotional or physical exhaustion leading to a diminished ability to empathize or feel compassion for others. It has also been referred to as Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS). Burnout is usually one of the top symptoms, along with mood swings, experiencing detachment, anxiety or depression, addiction, and more.

Compassion fatigue is the result of working directly with victims of disasters, trauma, and illness, and therefore can affect many different people in both professional settings and otherwise. Some of the people it can affect include first and foremost, healthcare workers and caregivers, police officers, child protective workers, journalists, lawyers, and more.

While I understand and (here we go) empathize with medical professionals who experience compassion fatigue, and I can absolutely understand how it can happen, it doesn’t make it okay to go on practicing medicine, or continue being a police officer, or whatever profession you’re in, if you’re experiencing it. It’s your responsibility to get the help and treatment needed for yourself and for your patients.

No one deserves less than 100%, and no one deserves to experience a doctor who has a lack of empathy. This is usually one of my first signs that it’s not the right fit with that doctor. Whether referred to as bedside manner, empathy, or compassion, it’s important for a doctor to exhibit it. Without it, you’re left with a shell of a medical professional who seems like a sociopathic robot who could not care less whether you get better or not.

A Little Empathy Goes A Long Way

We’re not asking for much here. You don’t have to bend over backwards or go out of your way to care. You can show you care in small ways, without breaking a nail. Just reach out to those who need it and show compassion. Show understanding. Show you believe us, and you’re there for us. It’s all we’re asking for.